Information on Smooth Fox Terriers

The following article was written by Riley's breeder, Mrs. Wendy Ellwood. It is an excellent explanation

of how the dogs assembly should correctly be made and work. This article was published in the

The American Fox Terrier Club Newsletter Fall of 2007:

Page 3

For viewers that have arrived on this page to find out WHAT makes a Fox Terrier a Fox Terrier, the following websites and article will be of great help. Sometimes it is hard to compute in ones mind just what 'breeding to the Standard' means. What the 'Standard' is, is written words describing the points of how the breed is suppost to look, act and move like - hence, making it different than....say, a Poodle, or a Lab. Each breed has it's own written Standard - and each Breeder interpets the Standard a bit differently - but the essense boils down to specifics, like balance, movement and disqualifications. The following will help readers figure out just what makes a Fox Terrier a Fox Terrier, and why breeding to the Standard is so very important.

This is an excellent example of a top quality Smooth Fox Terrier

Information on Smooth Fox Terriers

Where Dreams Come True

Commencing at the hind-end, rather than more appropritely at the head is a tad wierd-but then I am from Down Under, which may explain the problem. It is akin to placing the cart before the horse; then tht is not an inappropriate analogy given that the hind-end is the driving force--the engine room if you will--of our Terriers.

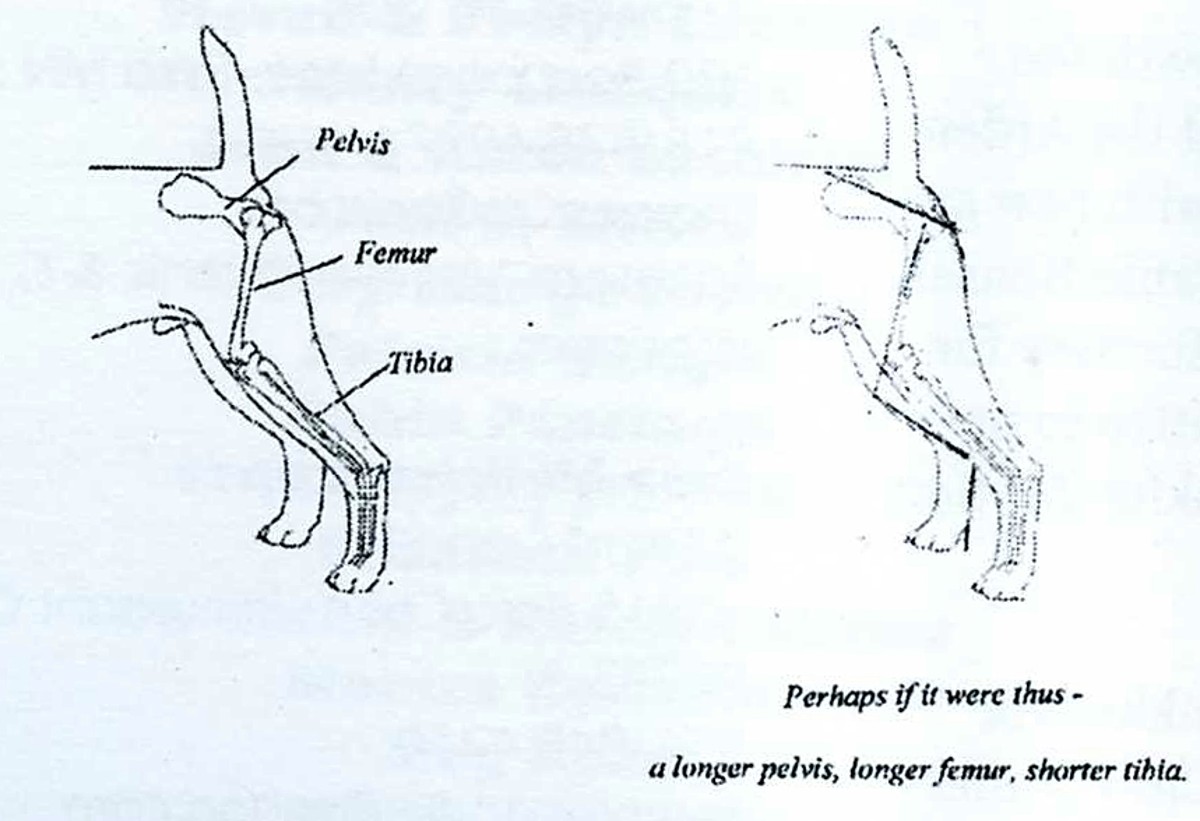

Studying these bones is like opening a magic box and discovering secrets that change your entire thinking and empower understanding. Here, beneath external view, lies the basis upon which hind outer shape and make and the ability to move well or otherwise is established. All is permitted or denied by the interaction, lengths, and angles of these bones--pelvis, femur, and tibia:

- hip width

- tail set

- wether there is little or pleanty behind the tail

- desired turn of stifle

- powerful or weak second thigh

- true or poor hocks

- length of stride

- A hind with driving force, rather than one that does all its work underneath (paddle) or all its work behind (kick back)

It is clear from Fig. A that the top of the pelvis is the hip and the bottom of the pelvis those bones which make the "bum behind the tail" or do you call them tailbones?

The pelvis

Feeling bones is how I examine dogs. I like to stand behind the dog and place my forefingers on the top of the pelvis (hips) and my thumbs on the bottom of the pelvis. Straight away I establish the width of the hip, length of the pelvis and that important, hoped-for presense of upward "tilt" of pelvis.

Below are some outcomes:

If the pelvis has good width:

- Good width across the hip will be obvious

- There will be a shapeliness (especially viewed from above) for there will be the appearance of a waist followed by a widening, strong shapely back end.

If the pelvis is narrow:

- The dog will be lacking hip width and appear narrow and of weaker construction

- It will also appear longer for there is little shapeliness from ribs to tail end.

If the pelvis holds its width throughout:

- Then fingers and thumbs will be in alignment (hopefully wide apart) setting the paradigm for the dog that maintains good width from top to ground.

If it dosen't and is wider at the top than the bottom:

- Then the forefingers sitting on the hipbones will be wider apart than the thumbs at the bottom of the pelvis and the dog will appear to 'pare off', losing width at or near the tail.

- There can be gradual decline in well-angled attachment between pelvis and femur and the consequent outcomes of femur/tibia and the dog likely to move very close from the hock down.

If the pelvis is long and the pelvis tilt upward:

- There will be plenty of 'bum behind the tail'

- The hip area will appear nice and flat

- The tail set will be 'bang on', free of any dip near the base of the tail.

If it is short and the tilt downward:

- The tail will appear set at the very back end of the dog

- The liklihood of a rise over the hip area and a consequent dip before the base of the tail

- The worst-case scenario--the dog that appears to be built under itself.

Consider the many variations possible within these parameters, and much is explained about the variety of differences we see in hind shape and movement.

Figure A

A closer look at the "Engine Room"

by Wendy Ellwood, Sealgair Kennels, Australia

The Femur

This bone is held ransome of its promise by nature of it's attachment to a good or poor pelvis. Having checked the pelvis, leave the thumb on the back of the pelvis and use the forefinger to locate the stifle joing and measure the length and angulation of the femur. Imagine extending that forefinger about an inch further and assess what a difference it would make to turn of stifle if that boine were longer.

- It needs to be of good length and well angulated

- If that most sought-after great turn of stifle plus plenty of stride length are to be achieved then this bone will assist in delivering the goods.

- When the femur is short there is less turn of stifle, and when short and attached to a downward tilted pelvis, it can, at worst, descent almost vertically. Couple this to a long tibia and some real problems enter the equation. Mor anon.

The Tibia

Such a fan am I of this fellow and what a difference it can make. Why is the tibia so often overlooked? He's such a helper, even as third bone down and dependent on all above, if he is just shorter in length with the consequent strong muscle, he will give some merit.

"Second thigh is one of the salient features of the body and

no judge should put up gundog or terrier unless thi part

of the anatomy is right up to standard."

Practically the whole propelling force of the hind limb is dependent upon the ability of the dog to straighten the hind limb from state of angulation into the state of complete extension and this is so dependent on the muscle power of a well-developed second thigh.

Of 'More anon"...some very real concerns

I wonder if you too are puzzled by the growing tendency, across many breeds, to select dogs with hocks placed way behind the back of the pelvis and for handlers to exacerbate this by stretching them out even further. I hear the words of the long-long mentor: "why would you wish it so?" Inexplicable to find an answer for such a dog, who by nature of his construction, is unable to work other than behind him.

Feeling bones vs. tapes and square

One of the benefits of 'feeling' bones is that you can assess in quite early puppyhood likely outcomes in adulthood. More particularly do I find this with the scapula and humerus: if the puppy is to have good lay of shoulder (scapula) you will feel that length and angulation very early -- even at 3 to 4 weeks. The hind too, a bit later--say, 6 to 8 weeks -- whether the pelvis has length and upward tilt, whether the femur will be longer than the tibia...it is all there to be felt. It is quite an esciting foray among a litter of puppies to commence measuring which has the longest scapula dn which is the best pelvis and then to watch progression. Generally, anotomical examination is both an interesting and reliable source of enquiry.